It was my first time maneuvering the streets of Ikosi-Ketu, Lagos. Trying to follow the directions I was given the best I could. I was going to meet Osaze Amadasun, an illustrator and painter, whom I have always admired albeit from afar. I alighted from the okada that took me into the inner streets where he resides. He welcomed me at his gate wearing a warm smile, a black T-Shirt, brightly-colored patterned Ankara pants and a pair of Crocs. There was a calmness about him that I would later find reflects in how he goes about his work.

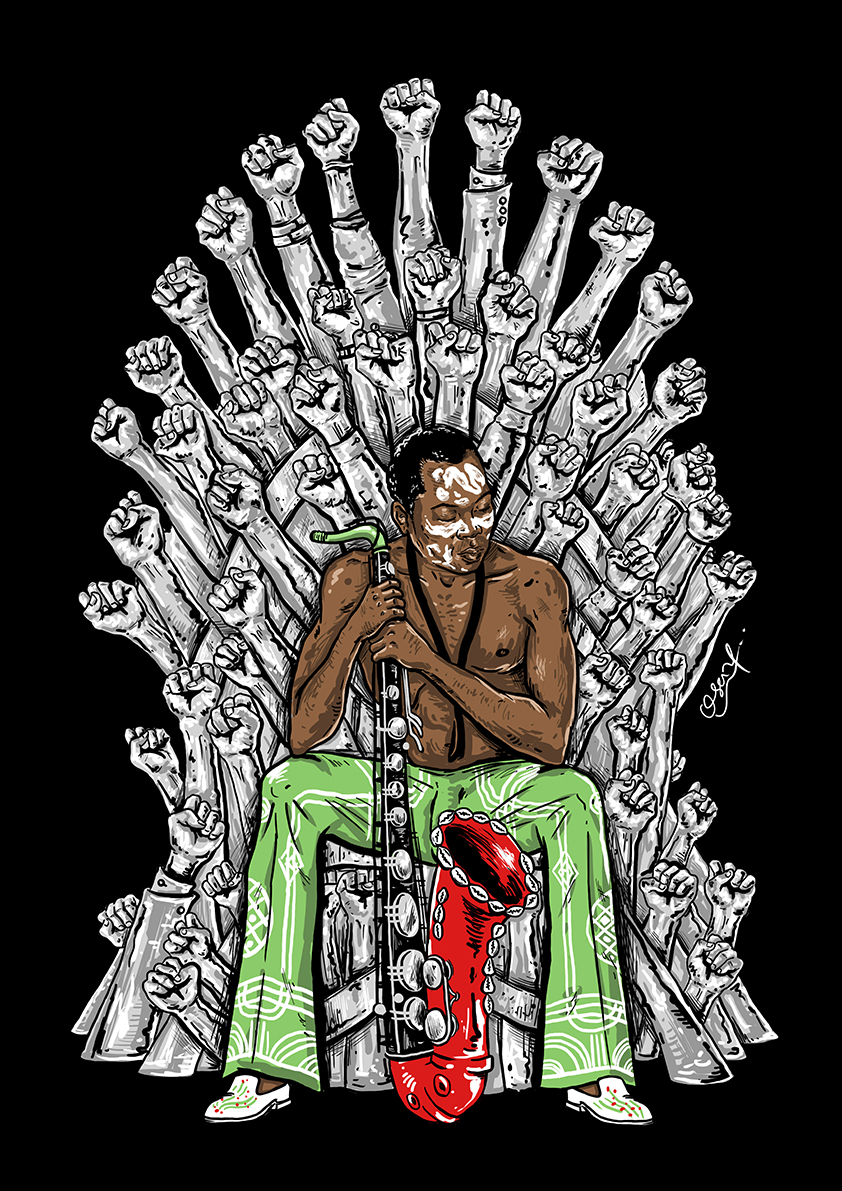

He showed me the workspace that also doubles as his bedroom. A painting of Fela sitting on a “Fist Throne” (in allusion to the Iron Throne from the popular HBO series, Game of Thrones) hung on the wall to the left of the bright-blue painted room. There’s a large table in one corner, a reading lamp clipped to its edge and some art materials scattered around it. His laptop makes its room at the center of the whole arrangement.

He went on to show me a commission he was working on – an offshoot of his series for Rele gallery’s Young Contemporary exhibition titled “Once Upon a Kingdom” (A collection of paintings depicting some key events in the Benin kingdom around the 16th century).

We spoke, at length, about his experiences before, during and after the exhibition, his connection to his native Benin Kingdom and limits he has had to overcome as an artist working in Nigeria.

Sheyi Owolabi: During our discussion, earlier, you mentioned that you don’t actually speak Bini. However, you decided to make the Benin culture a part of your latest project. Why?

Osaze Amadasun: For me, how this whole project started was kind of like an accident. When I was in the university, we had a project we were working on and we were to design a theme park. So, what I chose to design was the Oba Esigie Memorial Park. It was centered around one of the Obas of Benin. So I got on the Internet and tried to look for inspiration and material. But most of what I was seeing were bronze works from the 16th Century that everybody already knew about and also the Queen Idia mask. I felt like that couldn’t be all there was to the Benin kingdom and Benin art in general. So I started doing more research. I could spend the whole day researching Benin art. Over time, there were certain names that popped up consistently. So I felt these were most likely some of the key players when it came to Benin art and history. From there, I was able to get books to learn more. I got one written by Barbara Plankensteiner titled Benin Art & Rituals and another one, Royal Arts of Benin. This began like 2015. Since then, I’ve been collecting data around the Benin kingdom. When I read all these things, I make sketches so I have different stories or themes I want to explore. So, when I got the opportunity with Rele gallery, I just pushed out what I had gathered over the years. That was what I showed at the Exhibition.

SO: The Benin kingdom, from which you hail, has a long history of artistic production dating back to at least the 13th century. Do you credit your early interest in art to this cultural pull?

OA: I don’t think it’s my culture that pushed me to be an artist. I spent maybe a year or two in Benin. I know I finished nursery school in Benin. So from like primary one to University, I did everything here in Lagos. I have always been interested in drawing and things relating to art. So I wouldn’t say one hundred percent that it had anything to do with me being from Benin. Like when I came to Lagos, I was always interested in how roadside artists did their work and how I can get my work to be like theirs.

SO: What made you decide to become an artist?

OA: Well, I will still have to give the credit to the roadside artists. There were lots of roadside artists when I came to Lagos. I think that kind of like pushed me to pursue a career and focus more on art. They were producing really good work from my own point of view and I wanted to get to that level. That was really it.

SO: You are well known for your illustrations and posters. However, what/who inspired your Danfo series?

OA: There is this artist, his name is Karo Akpokiere. He is based in Berlin, Germany. When I got to know him, he did lots of Nigerian and particularly Lagos-inspired illustrations. I found his illustration style and rendering technique interesting. Even more interesting were the stories he was gathering because they were centered around what’s happening in Lagos and Nigeria at large. I guess that kind of rubbed off on me. My day-to-day experiences also had an influence. I move around in Danfo buses a lot and I thought, what can I do with this experience or with this typography? That was how it started. If you go down my Instagram page the first things regarding that was just me drawing maybe Eyo arts. Then I broke away from that and I started adding my own elements. Maybe I think of a word or a phrase, then I find a way to make that into a poster. It’s still something I am looking to explore more. But it is on hold for now. Those are just the first set of drawings I have done relating to that.

SO: Can you share some things you discovered while working on “Once Upon a Kingdom” that made you feel more connected to your Benin heritage?

OA: What I can remember from when I was in Benin are just flashes of images, a scene or two that, maybe, happened. However, when I was reading on some of the bronze works and festivals, those flashbacks began to make more sense to me.

SO: Can you go into more detail about the process from the beginning of creating the “Once Upon a Kingdom” series to the Young Contemporary exhibition?

OA: Okay, I mentioned earlier I had been doing some research since 2015, I wrote down some ideas for drawings and, possibly, exhibitions. The works I showed at Rele gallery were actually meant for my personal exhibition. I pitched the project idea to an artist and he said I needed to do a lot more research on it. Which was actually true. I wasn’t very knowledgeable on the subject matter at that particular point and the idea needed fine-tuning. After a year of fine-tuning the idea, I got a mail from Rele gallery asking if I was interested in participating in the young contemporary exhibition and for me to submit a proposal so they could consider if I could get in or not. So, I just pushed everything I had been working on to them. They got back to me that they were interested in it. That was how I got into that.

The hard part was knowing the story that you want to tell and composing the work in a way that makes sense to people. I am not an abstract artist. Even if they don’t totally get what is going on, I still want them to have an idea of what I am trying to talk about in my artwork.

SO: How was the series’ reception at the exhibition?

OA: The reception was really great. I got to hear different peoples’ point of view on these events that people don’t know happened back then. People connect with or remember images faster than words. For me, it was a great experience. I had to narrate the stories a couple of times. It was tiring, but it was worth it. I put everything together in a document so whenever anyone reaches out to me I can send it. So they can read up on it. There are also references if they want to do extensive research on it.

SO: Did you sell all your artworks from the exhibition?

OA: Yes, I did. (laughs)

SO: In a video introducing the work you were going to showcase at the Rele Art Foundation, you cited the incompleteness of the documentation of ancient Benin brass casters. Can you explain what you meant?

OA: From what I could see from my research, there were certain key events that didn’t have a picture to represent them. To me, it seemed off. There was a King that got baptized but, in the bronze works, there was no depiction of that. I felt that was a very important event. So, what I did with the exhibition was highlight some key events. I don’t even know if they were recorded. We only know what’s shown to us. Maybe it’s hidden in someone’s private collection, we don’t know. Basically, I just picked what I felt was important and I created them.

SO: Essentially, you were trying to fill a visual gap.

OA: Yes, you could say that.

SO: Late last year, a delegation from Easter Island petitioned the British Museum to return Hoa Hakananai’a which was stolen in 1869. The governor of Easter Island, who led the delegation, commented amidst tears “We are just a body. You, the British people, have our soul.” Do you feel the same way towards stolen African art?

OA: I share the same point of view. It doesn’t make sense to take someone else’s artwork and not return it. Their own point of view is that those works will not be kept or handled properly. If we want to destroy them, you shouldn’t have a say. It’s like I buy something, then someone comes to take what I bought with my money and say it’s because I will not handle it well. It doesn’t make sense.

SO: What do you think can be done? Do you think the government should get involved?

OA: I think the government is already involved trying to get them on loan after the Museum in Benin has been constructed.

SO: Artists generally tend to have a way they describe their style. How will you describe yours?

OA: Different artists have their own style. I am coming from a background of Architecture and Graphic Design. When you are designing a logo for maybe a law firm, the style or form of the logo will be different from say a logo for a kiddies’ party. The use of colour, shape and all will be different. The way I approach my artwork is practically the same. I don’t approach it from a painter’s point of view. It’s more from a designer’s point of view. If I am creating artwork for a merchandise or product, the way I will approach it will be different from creating a painting to hang on the wall.

I don’t really think about style. I just do my work and move on.

SO: Your work can get intensely political. You have many illustrations featuring the Afrobeat legend Fela Anikulapo Kuti. I particularly liked the one in which Fela sits on a “Fist Throne”. Would you say you are a fan of Fela?

OA: Personally, what I like about Fela was his style of music, the arrangement of the drums and all, the message he passes across and how he was able to push the African (particularly the Nigerian) narrative and give it international appeal. It’s something I also strive to do with my own work. Going back to the Benin project. How do we present these ancient things and make them appealing to the international audience? That’s basically it.

SO: Most people have come to associate Fela with politics and “struggle”. What’s your opinion on art that is political? Do you think visual art has the power to influence people as much as Fela’s music?

OA: Definitely, art can influence people. One four-year-old boy can look at your art, be inspired by it and say “I see myself in this work of art”. Art has driven and can drive political movements.

SO: Do you think artists have to be political?

OA: Like music- I don’t think people should make just music that’s talking about the country. People – what do you call them? Shepeteri boys (laughs) – make music to just “vibe”. I think everything is fine. People create art for different reasons. Some create to address issues in society. Personally, I think everything is valid. I don’t think one form is higher than the other. Just do your thing.

SO: You’ve been in the Nigerian art space for a while. What do you think are the limits or challenges you have to surmount just to get to where you want to be?

OA: First of all, getting materials and useful books that you would need to advance your skill is quite difficult because they don’t sell most of them here. So most of the time, you have to order them from the US, UK or Germany and, obviously, the cost of shipping and all have to come into play. So that has been one aspect.

Another will be production. Getting the quality that you really desire can be hard to get here. Let’s say you want to produce something for a T-Shirt or you want to make a pattern to print and put it out there, it’s relatively harder to get vendors that will give you the right quality. At the end of the day, you’d have to look to China or somewhere overseas and then shipping costs and the Naira to Dollar rate come into play again. It is discouraging.

SO: You don’t face challenges with people trying to poach or devalue your work?

OA: I mean, it’s always there for everybody. People trying to devalue your work. Trying to give you a lower price than what you are asking for. People taking your work without your permission. I’ve found that if you keep on dwelling on it, it’s not always the best. Do the work. Make as much as you can. Move on to the next thing.

SO: So, what are you working on next?

OA: It’s still going back to the Benin project. I have a couple of other series that I would like to paint. I just haven’t had the time yet. I just released a deck of playing cards centered around Benin art.

We know about the Benin bronze casters but I’m trying to see how can we present the culture in a way that people in the modern times can relate to. That is also something that Japanese people have been able to do with their ancient art form. They’ve been able to diversify and push it into different streams. From fashion shows to 3D toys to gaming and animation.

SO: Thank you very much for your time, Osaze.

OA: You are welcome.

Osaze Amadasun

Osaze Amadasun is an artist of creative elasticity whose artistic mediums cut across drawing, painting, illustration and graphic design. Osaze first trained as an architect graduating with a BSc. in Architecture in 2014 and went on to receive a Master’s Degree in Environmental Design in 2016, both from the University of Lagos. His works reflect the diverse culture of His environment and He shows a keen interest in documenting and storytelling through his art.

Over the years, Osaze has undertaken various art projects illustrating, designing and creating for high profile organizations. He recently got commissioned to create murals for the NG_HUB building, Facebook’s first flagship community hub space in Africa located in Yaba, Lagos. He also worked on ‘Say my Name ‘ a children’s book celebrating cultural diversity and ‘Bini playing cards’ which pays hommage to the ancient kingdom of Benin and its classical works of art. Osaze’s work has featured in the Guardian Life, Reuters, Konbini, Blanck Magazine UK, Art-X Live, amongst others.

This entry appeared in The Limits Issue