Agbowó Magazine

Editor's Note

About two years ago, Afridiaspora, an African literary magazine, published my poem - “An Extrapolation of Four Names”. The poem, divided into four stanzas, sought to give extended interpretations, in verse, to four names. The names – Ikulamberu, Ikuforijimi, Ikuemenisan, and Ikulala – are all prefixed with Iku-, the Yoruba word for death. For the fourth name, I write- “Death is not a small thing/It fills 79 by 24-inch caskets/It fills 6 feet gallows/It fills 25 thousand mile planets/Death is not a small thing”. Upon the poem’s publication, I shared the link to it on my twitter feed, eager to see how it will fare in the world. Roughly eleven minutes later, the poet Tade Ipadeola responded, suggesting, since I didn’t include diacritics, another extrapolation for Ikulala- “Death is the boundary”. I immediately thought this would have made for a more interesting extrapolation and rued not thinking about it first. It was this memory that first cropped up in my mind upon the selection of “Limits” as the theme for this year’s issue of Agbowó. Limit, from the Latin limes, meaning boundary. Death as a boundary.

The idea of death as a boundary or limit dates as far back as Socrates. In one of Plato’s dialogues, Phaedo, Socrates is about to commit state-sanctioned suicide and is persuaded by his friends to escape into exile instead. Socrates then proceeds to paint death as something the philosopher should not only be unafraid of but also embrace because death is the unshackling of soul from body. The soul, constantly seeking truth like all philosophers must, is constantly limited by the body which is too drawn to earthly desires of food, entertainment, sex and so on. For Socrates, death is, thus, the breaking out of the soul from the boundaries of flesh in the direction of truth.

But for many African cultures, this dichotomous existence – the either here or there that exists for Socrates – does not always hold. In some belief systems, like those in which the abiku or ogbanje is a possibility, the limits between death and life are mere suggestions that can be traversed back and forth at will. The exploration of this particular boundary has produced many pieces of glorious writing among which number Soyinka’s “Abiku”, Clark-Bekederemo’s poem of the same title, Akwaeke Emezi’s Freshwater and Ben Okri’s famed trilogy. In Okri’s The Famished Road, which was awarded the Man Booker in 1991, the major character, Azaro, named after Lazarus, is one of such spirit children. For Azaro, the borders between life and death are not frequented only by fainting and fits of illness but are collapsed all around him. In one beautiful sequence of words, Azaro is being pursued by Madame Koto and as he flees, we see a blurring of the limits between the physical and the metaphysical. Everything is co-mingling, he even comes upon a gate locked not by padlocks but by seven incantations. Reading that passage from Okri made me pause and wish I was an artist – a gifted one – so I could paint what was written and title it The flight of Azaro. Within this issue, Adé Sultan Sangodoyin’s A Language of the Unconscious melds, in the same manner, dream and reality. I was not surprised to see, in his short bio, a mention of Okri.

For Oba1 Adeyeye Enitan Ogunwusi, the Ooni of Ile-Ife, this blurring of the boundaries between both worlds is not a preserve of spirit children. Sitting, alongside members of my extended family, at his table one October afternoon, he bids us to tell him the number of “us” in the room. I count and supply a physical answer which he laughs off in favour of his metaphysical estimate of “thousands and thousands” which includes the spirits. I, and I suppose others, don’t look very convinced. He then asks us why we think babies cry without cause and, in almost equal measure, laugh untickled. A smooth maneuver since we cannot ask babies for exact answers. He then posits that it is these unseen and yet ubiquitous spirits that are responsible. Some clown and the baby giggles. Some are mean and the baby weeps. He says all babies preserve this gift of seeing beyond the border till they start to speak. Once they speak their first word, the special eye shuts forever. He goes on to add that only the initiated, among adults, can see the true multitude of spiritual events constantly taking place around us and that if an ordinary person were to suddenly behold it, they’d run mad.

Madness. Insanity. As a teenager at the University of Ibadan, I was momentarily obsessed with the idea of insanity. I intended to compile a private anthology about the subject. It would include poems, a story and an essay propounding a theory. The theory, which I thought groundbreaking at the time, was about the paradox of healing from insanity. The cornerstone of the idea was that since healing a madman will involve getting him to see that he was mad all along and since a madman by definition staunchly believes in his own sanity, it is impossible to drag him over the boundary. The inspiration for the theory was, I think, from Zeno’s paradox which is about the impossibility of getting from point A to B. But the evidence was firmly against my theory. Of course people regain control over their minds. I concluded that treatment was as a result of a transformative vacuum at the limits between sanity and insanity. Limits are the places where the miraculous occur. I gave up on the project since it wasn’t heading where I wanted and soon the notebook became scrap paper for stoichiometric calculations and, subsequently, disappeared.

Masquerades are also creatures of limits. Asides from the physical interpretation of masquerades pushing their bodies to the limits of gymnastic and calisthenic performance, there is a symbolic interpretation. Masquerades, in many African cultures, are thought to be inhabited by spirits of the ancestors. The muscles of the living, animated by the energy of the dead. So that when masquerades dance and somersault, they do so on the borders between here and the hereafter.

But the theme’s interpretation is not limited to metaphysical, psychological and geographic borders. Calling for submissions, we suggested other ways the theme could be interpreted – as an exploration of impediments, as a treatise on bodily autonomy and a call to stretch artistic imagination beyond what is currently available or acceptable. The writers and artists whose works appear within these pages responded with a thematic variety that confirmed to us the robustness of the selected theme. In Jarred Thompson’s Scabbing, limits are sexual. In Fatima Okhuosami’s Picturesque, they are religious. But I should stop now. I suspect that by these “spoilers”, I am robbing you of that immense pleasure that only reading themed magazines give; the “Aha!” moment when one realizes why a work is included.

Moyosore Orimoloye

Akure,

July 2019

1 – Yoruba King, Traditional Ruler

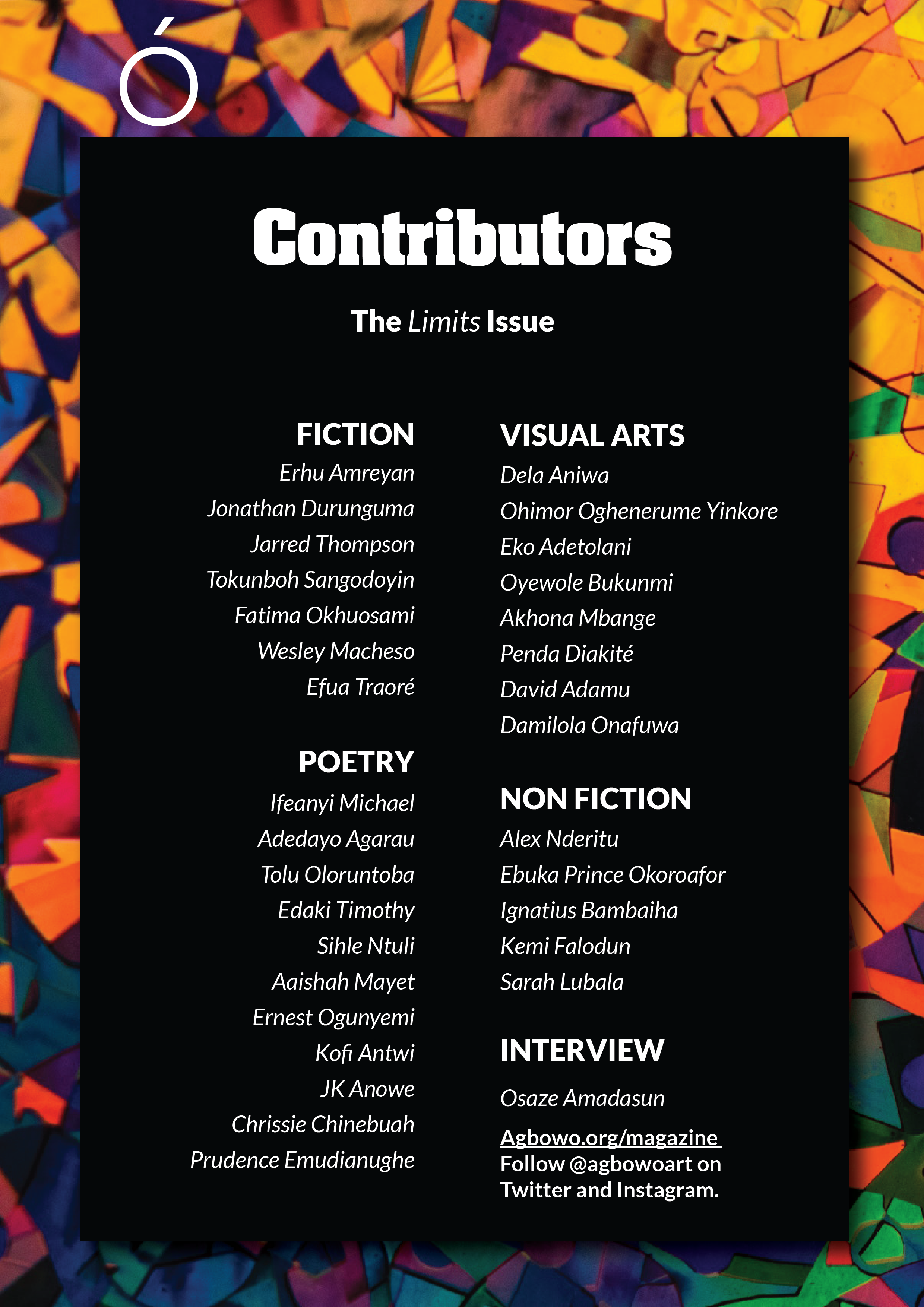

Content List

Fiction

- Made of Water - Erhu Kome Yellow

- I like the sound of that - Jonathan Durunguma

- Scabbing - Jarred Thompson

- A Language of the Unconscious - Tokunboh Sangodoyin

- Picturesque - Fatima Okhuosami

- A Night at Ikhaya - Wesley Macheso

- Heaven S(c)ent - Efua Traore

Essays/Non-Fiction

- How Pepe Minambo Went Beyond Limit - Alex Nderitu

- Beyond Dreams - Ebuka Prince Okoroafor

- A Rant about Society’s Reluctance on Transgender Discrimination - Ignatius Bambaiha

- A Souvenir of Me - Kemi Falodun

- My Aunt Tried to Exorcise Me and Other Thoughts on Liminality - Sarah Lubala

Poetry

- Brittle - Ifeanyi Michael

- Anorexia Nervosa - Adedayo Agarau

- Near Field - Tolu Oloruntoba

- How Do You Start A Revolution - Edaki Timothy

- Free State - Sihle Ntuli

- The Solace of Scapegoats - Aaishah Mayet

- A Conversation with my Father - Ernest Ogunyemi

- Southern Gospel - Kofi Antwi

- Aubade with Purgatory - JK Anowe

- The Pacification of An Afro - Chrissie Chinebuah

- When They Asked How You Lived - Prudence Emudianughe

Visual Art/Photography

- The Floating Kid - Dela Aniwa

- Limitless - Ohimor Oghenerume Yinkore

- Despair - Eko Adetolani

- The Hauler - Oyewole Bukunmi

- Siblings - Akhona Mbange

- Consumer - Penda Diakité

- Black Noise - Penda Diakité

- Afrofvtvre - David Adamu

- Street Deity (Egungun) - Damilola Onafuwa

Interview

- Osaze Amadasun