I am a small-time Badagrian, and that fact tends to shape my worldview and outlook in a number of ways. But before I relate one little way in which this aspect of my background would sometimes mould my thought and imagination, I should provide a little detail about who, to my mind and for my purpose here, a Badagrian is.

By way of nationality, a Badagrian is Nigerian, specifically a native of Badagry, a coastal town in present-day Nigeria’s south-western extremity. Badagry is a border town, adjacent to Benin Republic’s Sèmè-Kpodji town on the west. As an Atlantic and lagoon-side slave port, Badagry was a crucially important depot of the transatlantic slave trade in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, I mean some 300 and 200 years ago. Indeed, its prominent role in the history of the transatlantic slave trade on the Bight of Benin, West Africa’s ‘Slave Coast’, was only latterly overtaken by its neighbour ports, Lagos and Porto-Novo, to the east and west respectively. However, the terrible trade is not the only historical conjuncture for which my hometown is renowned. Badagry is also popular for being an early foothold of Christian mission in and British colonisation of what became Nigeria. Around these three epoch-making sagas, considerable memorialisation, monumentalisation and place-making have been and are being done across the town.

With that in mind, I think it seems fair to say, metaphorically, that every Badagrian who grew up in Badagry suckled on memories of that trilogy in Nigeria’s history—the transatlantic slave trade, European Christian mission and British colonisation. And this is one kind of lifelong suckling, some sort of breastfeeding that one hardly ever gets weaned off. Right from infancy, motherland fed us this memory-milk in many different forms—stories, fables, idioms, songs, dances, festivals and remembrances, and, more concretely, as museums, monuments, historical sites, public arts, relics, memorabilia and curios. The thing is, everywhere you turned, your entire senses caught something of the varied forms in which those distant yet intimate historical episodes and memories of them come at you. Those pasts and their memories were constantly retold, re-imagined, re-invoked, and re-enacted. A visit to any of the three museums in Badagry will give you an idea of what I mean. Essentially unprofessional as many of the curators and tour-guides are, when they begin their umpteenth recital, they will come off to you as some master Malian—add, if you like, an ‘r’ in-between the ‘a’ and the ‘l’—griot or minstrel carrying on his or her trade at their best!

Coming from this background, I am here now standing by the shores of Lake Geneva, smooth, colourful pebbles beneath my feet, as I stare at the gentle swans and gulls playing on and in the waters, and at the Alps’ snowy caps in the horizon. Here, almost 3,000 nautical miles between me and motherland and her many children; here, fondling the coconut-shell pendant of this thing around my neck, reminiscing about my childhood, as I type these words into my phone with the other hand. This crescent-shaped waters remind me of the Atlantic, the Badagry bit of it. It reminds me of how, as a short black boy, I would sit barefoot, under the steaming golden rays of the beach-sun, for the sun takes on some kind of magical life at the beach, a magic that is only best experienced first-hand and can never truly be captured through words or pictures. Here I am regurgitating and ruminating on the years of memory-meal—literally so, as would an impala chewing the cud on tender, lush grasses. I am thinking back on how I would sit in the moist, fine sands at the ‘Point of No Return’ on Badagry’s Atlantic coast, and build sandcastles, and run after tiny sea-crabs and after my own shadow.

I reminisce the many different stories we were fed, of how scores of thousands of the fore-fathers, -mothers, -sisters, -brothers and -children of diverse peoples with whom I would now identify as my fellow nationals were gruesomely loaded onto ships that were no better than Nazi concentration camps and carted away into the terrible agonies of the slave plantations in the Americas. I remember how we grew up hating to even see anyone around us eat sardines, not to mention have one ourselves. Because the sardine’s jam-packed-ness and oily ‘mess’ was the simplest way the awful conditions in the belly of a slave ship were illustrated to us. I think back on how what I now know to be loads of Sargassum sea-weed from the sea’s abyss once washed ashore, and our then-bachelor uncles told us those were smithereens of the many thousands of our kinsfolk who never survived the Atlantic crossing trying to gratify their homesickness.

I recall once when, while picking firewood with my mother in the extensive coconut plantation adorning our beach, I witnessed an unfortunate scene where a coconut fruit suddenly dropped on the head of an unsuspecting boy and he momentarily fainted. When we got home, I asked my mother why these many drupes of coconuts could not have helped us out by raining down heavily on the enslavers and slave merchants who came to capture our peoples. Mother then made me realise that the coconut trees were all late-comers to the scene; that they were only planted in the dying days of the slave trade. How much really can coconut trees do in the face of canons and swivel guns!?

Here I am, thinking back to those times when I would sit in the beachside zephyr and I would think of the Atlantic as a really big reservoir bearing the roaring rage and strident echoes of the hues and cries of those countless enslaved peoples being hauled away. I am now recalling, with much catharsis, how I would sit there and think that the ocean’s waters must have been salted by the tears of many a wailing shackled captive. And even today, each time I find myself at a beach, any beach for that matter, specifically the shores of any mass of saltwater, I still think of home, and of my peoples, forcefully carted away, seasoning the waters with their tears!

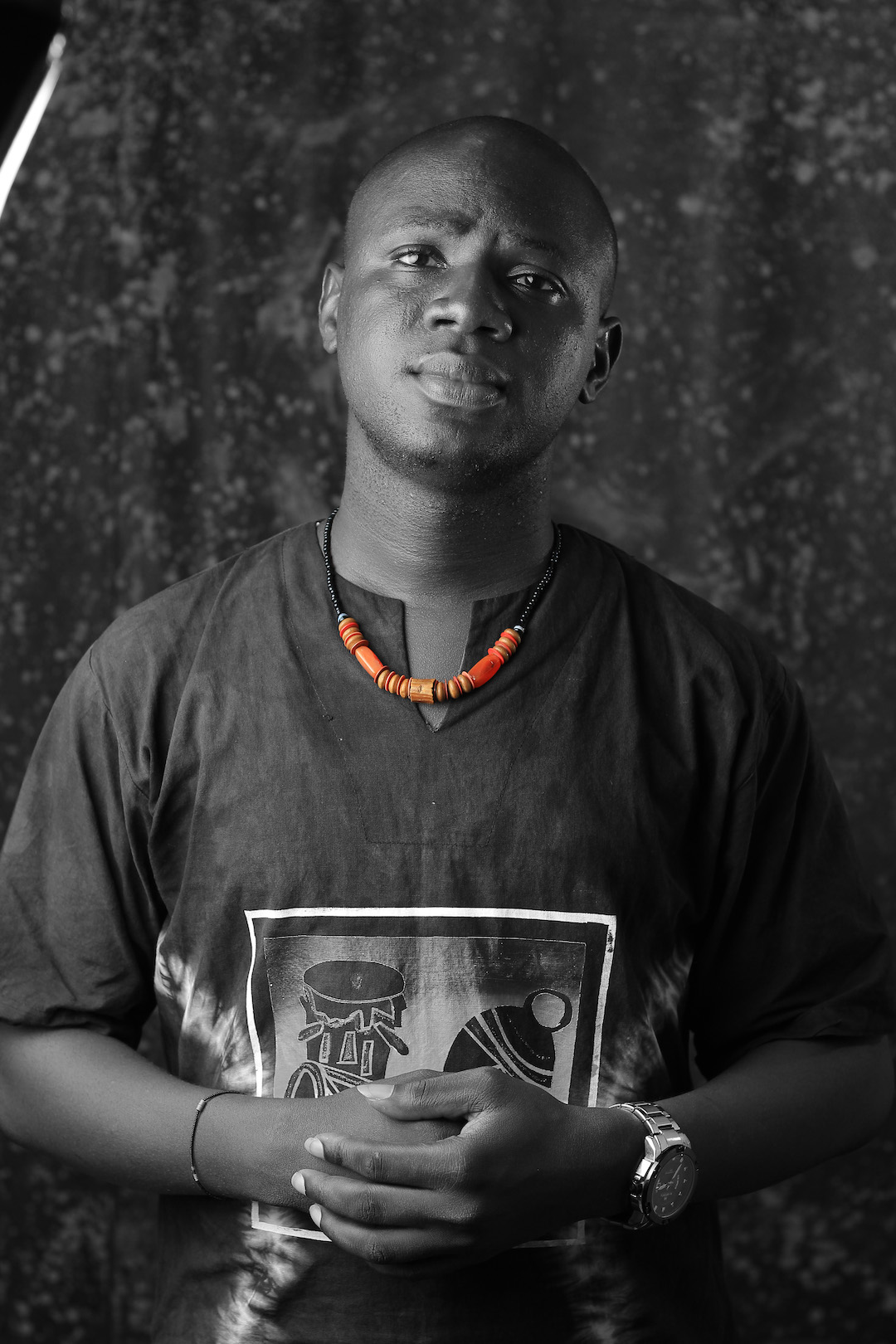

Ṣeun Williams

Ṣeun Williams is a student of history, of yesterday’s memories and everything prior to the now, who fancies weaving webs with words, and groping at things at intersections of time-space by means of/through lenses. He is currently PhDing about some ‘meaty’ part of Lagos history in the comme ci, comme ça of Geneva. He can be caught roaming the web via @WheelHelms.

This entry appeared in The Memory Issue