DOWNLOAD BELOW

[wd_hustle id=”5″ type=”embedded”/]Contributors’ List

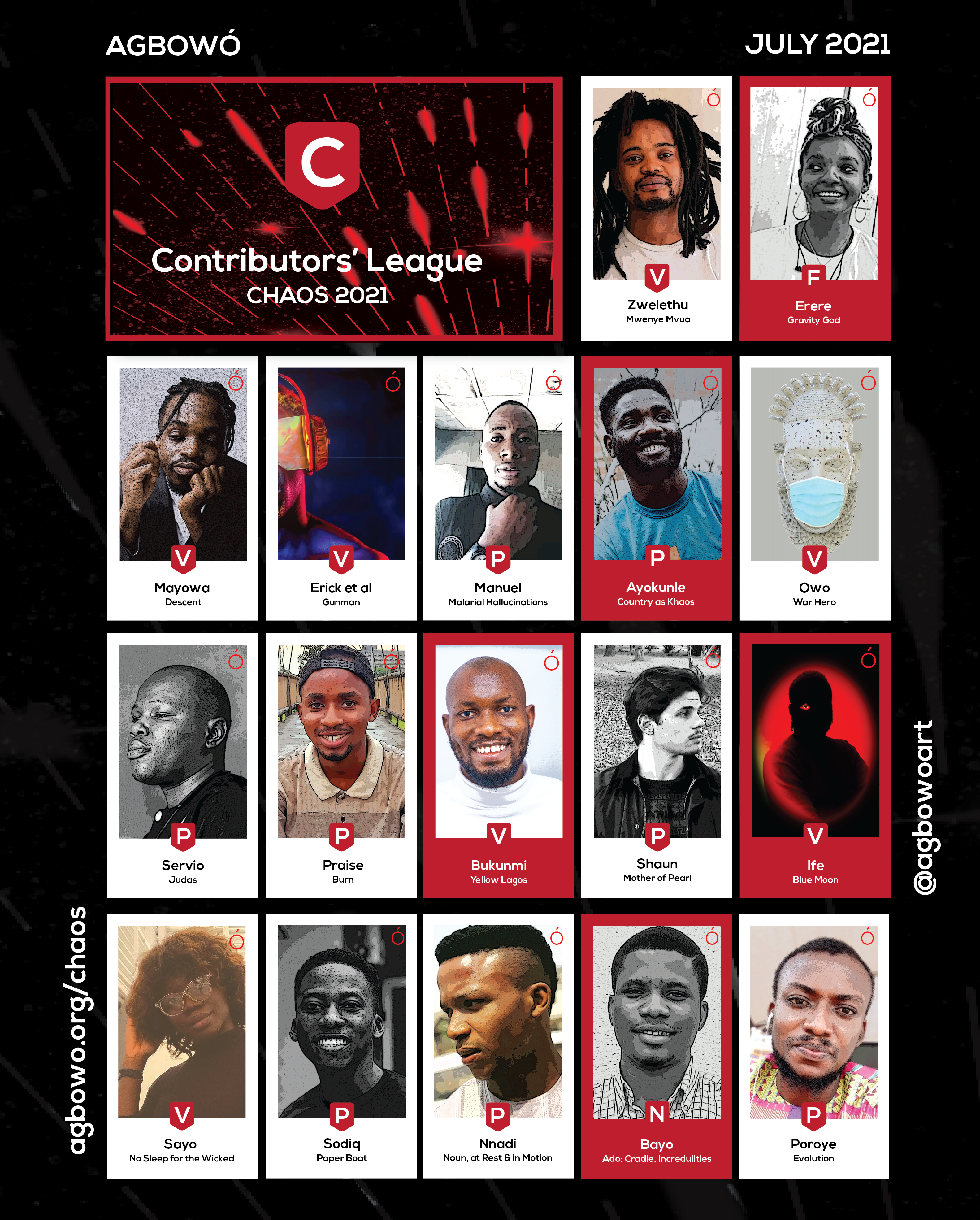

Contributors

POETRY

| S/N | NAME | WORK |

| 1 | Sodiq Oyekanmi | paper boat |

| 2 | Shaun Pieter Clamp | Mother of Pearl |

| 3 | Ayokunle Falomo | Country as Khaos |

| 4 | Praise Osawaru | burn |

| 5 | Servio Gbadamosi | Judas |

| 6 | Nnadi Samuel | Noun, at Rest & in Motion |

| 7 | Oluwatobi Poroye | Evolution |

| 8 | Olumide Manuel | Malarial Hallucinations |

VISUAL ART

| S/N | NAME | WORK | |

| 1 | Bukunmi Oyewole | Yellow Lagos | |

| 2 | IFEOFDESIGN | Blue Moon | |

| 3 | Sayo Ajetunmobi | No Sleep for the Wicked, To be or Not to Be | |

| 4 | Zwelethu Machepha | Mwenye Mvua | |

| 5 | Mayowa Alabi | Descent, Razzle Dazzle et al. | |

| 6 | Owo Anietie | War Hero | |

| 7 | Eric Manyawa, James Gikonyo, Sagallo | Gunman | |

| 8 | |||

FICTION

| S/N | NAME | WORK |

| 1 | Erere Onyeugbo | Gravity God |

NONFICTION

| S/N | NAME | WORK |

| 1 | Bayo Aderoju | Ado: Cradle, Incredulities |

INTERVIEW

| S/N | NAME | |

| 1 | Mayowa Alabi | |

| 2 | Owo Anietie |

Editor’s Note

I have often imagined aliens watching games of football from their cosmic perches. How must it be for them? What questions – if questions are a concept among them – might they ask? Why are they darting in pursuit of that sphere? Why, after all the struggle to get it, hasten to kick it away? After 0.00017 revolutions, why do they simply leave the rectangle? By seeing enough games, they might slowly map out the rules, but what about the concept of sport? To the other, everything is nebulous – chaotic.

In this way, one arrives at a definition of chaos that rejects it, casts it as temporary, subjective, as an ignorance of the rules, a lack of parameters by which to make appropriate forecasts, and a substrate for the ever-probing eyes of science and measurement. If the seemingly chaotic scattering of sand can be modelled by equations, why not hedge our bets on social psychologists figuring out the workings of a mob? The scientific method thus avers that chaos is merely a precursor to understanding. But can such a definition succeed?

Some will argue that it has–we cannot, after all, deny the constant erosion of external indeterminacies in bacteria, the oceans, and the cosmos. With every new publication in Science, more details about the details of the living universe emerge. But what about our internal indeterminacies? What about that inner chaos that is stirred when the simple “how are you?” is posed to us? What instrument will reliably and reproducibly measure the weight of our joys? What equations will help us properly fit the data, and allow us reach a numerical understanding of ourselves?

In trying to describe “feelings”, one can of course whip out the scale – “how much do you want me, on a scale of one to ten?” But one quickly realizes the ineffectiveness and futility of numerals, that language of precision, in this regard. We sigh, we beat about the bush, we resort to linguistic approximations, but the things we want the most to say, remain unsaid. After the fact, we could have always said it better. And if Heidegger is to be believed and “language is the house of being”, we are housed in approximations of experience, are filled with approximate emotions and our approximations pile upon each other and domino into that ongoing scream readily observable in the latency of our angsts. Is it any wonder then, that we go through a list of methods to suppress this internal chaos? That we run towards the mindlessness of manual labour, the overexertion of exercise, the escape of meditation, the automatism of mantras, and other semblances of order? While artists are not quite unlike us in running, it is within that precocious space of the chaotic and ambiguous that they must return to in order to find work.

The works that populate this issue–our most compact yet–reflect this attitude of the artist, working in an area characterized by an absence of certitude. Behind the eyes of the poet-speaker of Olumide Manuel’s Malarial Hallucinations, we find the relentless lunges and re-lunges at description that working in this space demands. And while that poet takes us behind eyes, the eyes in Sayo Ajetunmobi’s portraits – to be or not to be and no sleep for the wicked – are impenetrable. Is that relief or defiance? Is that sadness or expectation? I have never given much thought to the inscrutability of faces. I can, after all, see smiles behind masks and catch the subtlest twitches of eyebrows. But the static nature of portraits demands a long gaze, and, with time, everything is questionable. Is that relief or defiance? Maybe it’s contemplation.

By embracing chaos, the artists in this issue cast doubts on the mythological truism of the act of creation, and by extension creativity, being a fashioning of order out of the chaotic – out of a formless world. They attest that, as long as humans and language exist, the world remains formless. While Bukunmi Oyewole’s photographs show that the formlessness may lay in the quotidian, Erere Onyeugbo’s Gravity god shows that it is present in even the most fastidiously documented and examined intimacies, and in Ado: Cradle, Incredulities, Bayo Aderoju leads us to what appears to be the precipice of an irrecoverable moment.

This issue, our fourth offering, also includes transcripts of interviews by Agbowó’s Sheyi Owolabi with Mayowa Alabi–the artist of this issue’s cover image, Descent and Owo Anietie whose portfolio, War Hero, draws on stories the artist learns from his mother about the Biafran War. Thinking about war, I am reminded of another commonplace antonym of the chaotic – the natural or normal. Czesław Miłosz, meditating on the subject in The Captive Mind, avers – “Man tends to regard the order he lives in as natural […] His first stroll along a street littered with glass from bomb-shattered windows shakes his faith in the “naturalness” of his world.” Like Miłosz, who challenges us to ask what world is truly natural, Anietie asks if a lone man, with only his “white horse” and his gods as possessions, going in search of family isn’t also a most natural thing.

But I tire of rendering these introductory exegeses which are, at their worst, authoritarian proclamations about how the works within an issue must be experienced and, at their best, merely well-mannered attempts at ordering the reader’s experience of the issue (an admittedly ironic exercise for Chaos). Rather, I should confess that all the works in this issue invite your participation and have no need for interpreters and the necessarily limited scope of our references. Art, after all, exists in the realm of dreams where all meaning is individualized. You must, therefore, walk into this open, and alone.

Moyosore Orimoloye

Minneapolis

July 2021