In the wake of Europe’s stalled restitution promises, which collide with Nigeria’s own season of desperate #Japa wave-driven brain drain, The Fire and The Moth arrives as a folk tale dressed as a thriller. There’s no soft landing: Ibadan-raised writer-director, Taiwo Egunjobi, follows Saba—a small-time smuggler who agrees to ferry a stolen twelfth-century Ifẹ bronze head across Nigeria’s southwestern border, only to discover that every road is a minefield. There is nostalgia and regret. And perhaps the sacred lessons of fire.

The landscape is oddly familiar, yet strange, and Egunjobi’s camera soaks the roads in mildew greens, rust reds, and the muted turquoise of oxidised bronze, nodding both to Roger Deakins’s desert restraint and the patina attached to the real heads first unearthed at Wunmonije Compound in 1938. Within the film, I question premonitions and predestinations. What, according to Taiwo Egunjobi, does reckoning mean?

What emerges is a slow-burn Afro-western whose true antagonist is greed: colonial greed that once spirited ancestral art to European museums, and contemporary greed that now tempts Nigerians to repeat the crime under the banner of survival. That moral loop—“we were robbed, now we rob ourselves”—has obsessed Egunjobi across three earlier features: In Ibadan, All Na Vibes, and A Green Fever, each probing what surfaces when failing systems squeeze ordinary people. In this conversation, I rifle through Taiwo Egunjobi’s private archive—old coup-era newspapers, Yoruba proverbs, and colour-grade notebooks—to ask why his characters keep running and what they think awaits at the border.

As his latest work of art – The Fire and the Moth hits the screens, Taiwo goes into conversation with Adedayo Agarau.

Adedayo: In his 2017 speech at Ouagadougou University in Burkina Faso, Emmanuel Macron promised to create conditions for returning African cultural heritage from France, stating: “I cannot accept that a large part of the cultural heritage from several African countries is in France . . . In the next five years, I want the conditions to be created for the temporary or permanent restitution of African patrimony to Africa.”

I find Macron’s approach problematic, as it seems to maintain a paternalistic relationship where Europe retains authority over African cultural treasures—deciding when to “lend them back” and when to reclaim them. In the same speech, he even suggested European curators had “saved those artworks for Africa by protecting them from African traffickers,” recasting colonial plunder as benevolent protection.

In The Fire and The Moth, you explore colonial legacies through Abike’s character and her desire for a share in Saba’s loot, the Ile Ife bronze head, which seems tied to internalized colonial values about whiteness. How did you approach colonialism as an “after-image” that continues to distort self-worth and identity in formerly colonized peoples? What were you trying to convey through Abike’s hunger for the bronze and the access to whiteness she confidently boasts of?

Taiwo Egunjobi: I think Abike represents a familiar figure, someone highly educated, well-positioned, yet still shaped by current-era attitudes and perhaps the lingering distortions of colonial identity. But what makes her more troubling is that, despite her awareness, she chooses to participate in the plunder. Her knowledge and access become tools, not for cultural change, but for re-plunder. Through her, I’m interrogating this economy of greed that often masquerades as progress. Are we truly ready to reclaim what was stolen? And if we’re not, when will we be?

Adedayo: Important questions, Taiwo. In Black Panther, the Benin bronzes become trophies of revolutionary justice—Killmonger steals in order to “return.” In The Fire and The Moth, the Ife head never even gestures toward restitution: Saba first agrees to smuggle it to pay his father’s hospital fees, then—nudged by Abike—imagines cashing in himself. By shifting the motive from national redress to raw survival-and-profit, you seem to trade Killmonger’s collective rage for the very “every-man-for-himself” ethic that haunts contemporary Nigeria.

Taiwo, was that deliberate? How did you want audiences to read the journey of the bronze—as a parable of individual hustle eclipsing communal responsibility, or as proof that colonial wounds now surface through personal desperation rather than grand gestures of restitution?

Taiwo Egunjobi: Yes, it was deliberate. I get very fired up about the rot beneath the surface; narratives around things of that type interest me a lot—and not just for practical storytelling aesthetics or the conflict engine that emerges naturally; you know what happens when desperation, personal ambition, and compromised morality collide, that interests me philosophically too. What is communal responsibility to us? True, Saba’s journey is less Killmonger and more Nigerian reality: The bronze becomes a commodity, just another thing to be flipped in a world that’s lost all reverence. That’s the tragedy. Not just that we’ve been robbed, but that we now do the robbing ourselves. Where is personal responsibility for current outcomes?

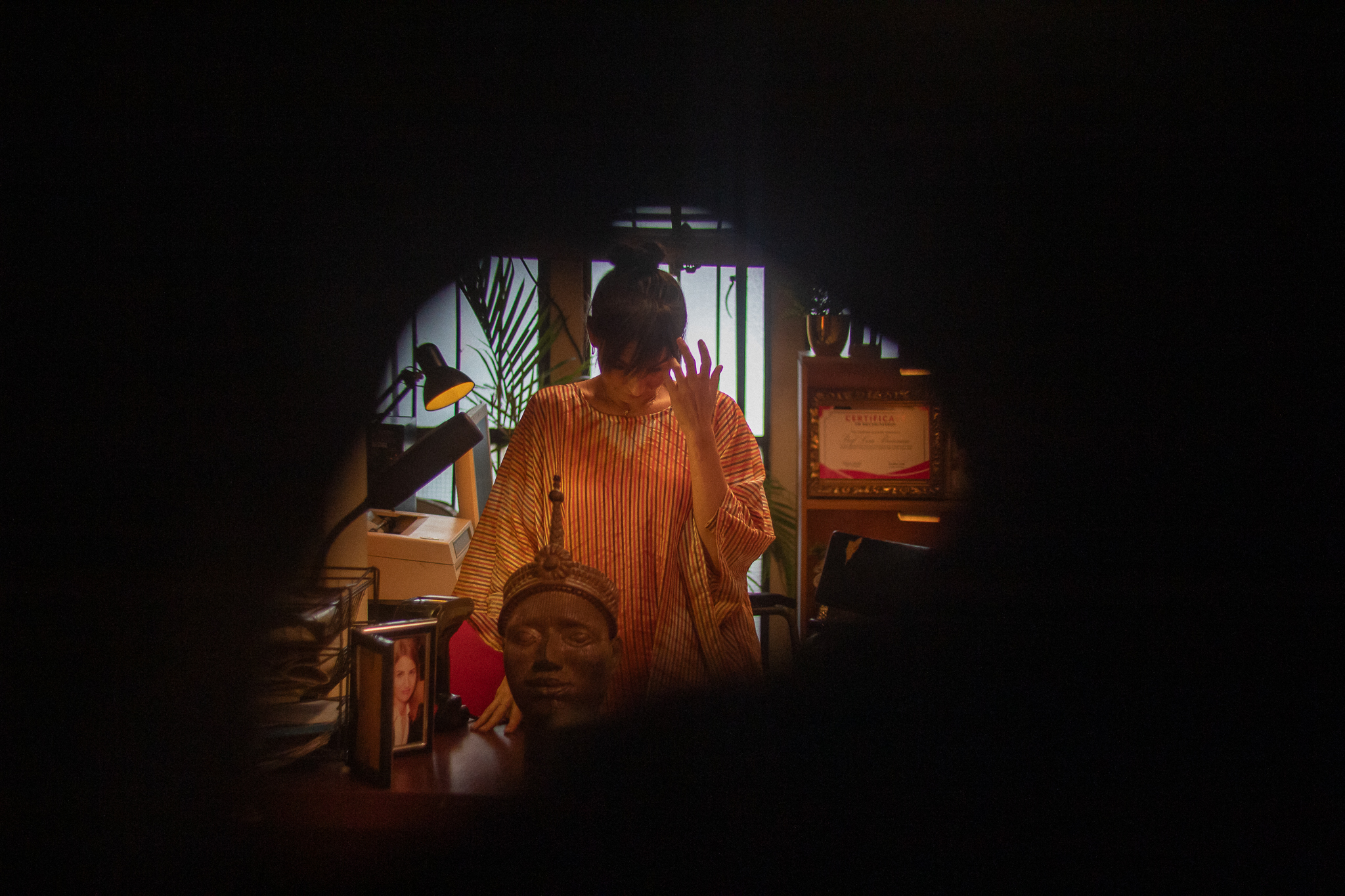

Adedayo: Cast by Yoruba smiths more than eight centuries ago, the Ife heads astonished colonial archaeologists precisely because their calm realism—striated cheeks, measured gaze—refused every crude stereotype of “primitive” African art. Yet a few weeks after their 1938 discovery at Wunmonije Compound, several were already on steamships to London and New York, inaugurating a supply line of desire and profit that your film explicitly mirrors.When you place one of those heads at the moral center of The Fire and The Moth, were you hoping viewers would still glimpse its original serenity—an echo of a court where brass once stood for cosmic order—or were you more interested in its after-story: the bruised patina of an object wrenched from ritual space and hustled along black-market roads not unlike Saba’s? How did your production design, blocking, and lighting let that ancestral dignity converse (or clash) with the clammy, diesel-fumed desperation of your frontier underworld? I’m curious whether, on set, you ever framed the bronze as a silent judge of the chaos swirling around it, or if you treated it purely as contraband whose meaning is now dictated by whoever can flip it fastest.

Taiwo Egunjobi: That’s such a profound question, and one that touches something central to The Fire and The Moth. There’s a moment in the film where the professor tells Saba that the Ife heads aren’t merely decorative or historical, they’re spiritual vessels that shouldn’t be trifled with. The “Ori is the seat of man’s destiny,” and that tampering with it is, in essence, tampering with one’s fate. That conversation quietly frames the entire moral architecture of the film. We didn’t shoot the bronze head with overly reverent lighting or visual cues, I actually wanted it to sit in the grime and desperation of the world around it. But we did lean into subtler tools, particularly sound design, to maintain a sense of awe. Whenever the head appears, there’s often a faint layer beneath the ambient mix: a low hum or even a distant metallic echo. It’s not something that announces itself, but it subconsciously shifts the space around it, as if the head is exerting some spiritual gravity. It was our way of signaling that this isn’t just an object of profit, it’s a presence.

Adedayo: Interesting, Taiwo, that you bring Yoruba cosmology and science into a film that also navigates greed and survival. Do you believe in predestination? If yes, how do you think that is working in this story? And why fire? Is there a relationship between the seat of the man’s destiny, the Ife bronze head, and the fire tank?

Taiwo Egunjobi : I do believe in destiny, but I also believe in choice. In Yoruba cosmology, your ori, your inner head, is the compass you chose before birth, but even then, you still have to walk the path, and your IWA is very pivotal. That tension between destiny and choice is something I think we live with daily as humans. So, in The Fire and The Moth, yes, you could say everything is drawn along that current, but the characters are still actively deciding, actively compromising. And every choice echoes

The Fire in this story is not just a device of destruction but it is also poetic, it is also spiritual, a Yoruba proverb goes thus, afopina to loun o pa fitila, ara re ni o pa; which basically means that moths, being drawn to fire, do get killed when they attempt to kill the flame of the lamp.

The Ife head is an object of religion; it is sacred, and ultimately, Saba’s destiny is altered irrevocably the moment he handles the head. So yes, the fire tank and the bronze head are connected. One is a literal vessel for fuel, the other a spiritual vessel for destiny.

Adedayo: Growing up amid the layered histories of Ibadan—a city where colonial rail lines, coup-era paranoia, and today’s frenetic hustle all overlap—you’ve said you became fixated on “people who are under immense pressure.” Your first feature, In Ibadan, trapped its hero inside that city’s unresolved past; All Na Vibes watched a trio of teens slide toward violence when every exit seemed blocked, and A Green Fever literalized greed as a “sickness” infecting anyone desperate for quick salvation.

Those stories unfold against a real-world backdrop in which more than 15,000 Nigerian nurses fled the country in 2024 alone, part of the wider japa wave of citizens sprinting toward any viable future. In The Fire and The Moth, Saba’s flight with a stolen Ife head feels like the darkest extension of that instinct: escape first, reckon later.

You once called greed “a sickness” that surfaces when ordinary people are cornered; now you give us Saba, a smuggler who runs not for justice but to buy his dying father time, then lets the fever of quick money rewrite his loyalties. What is your fixation with this human deficiency, and why does it make so much artistic drive for you? Can you talk to me about a moment in your own life—something you witnessed in Ibadan, or perhaps encountered while studying psychology at the University of Ibadan—that convinced you the most honest way to diagnose contemporary Nigeria is to follow a character already sprinting for the exit? See Abike? See Olarotimi Fakunle’s character, Opa? See William Benson’s character, Teriba? How did that conviction shape the moral compass you handed to Saba, whose run feels both personal and emblematic of a nation caught between collective wounds and individual survival?

Taiwo Egunjobi: I’m always quick to talk about how I grew up in Ibadan, around very old books, old news magazines and quite an old professor of a dad, I grew up understanding that things never really change with the Nigerian psyche; those news articles from the ’80s and 2000s all sort of read the same: talk of failed infrastructure, dashed hopes, small scandals repeating themselves under different names. You start to realize that public greed is rife, pressure is constant, and there is no release valve, and when people are cornered, the worst and desperate parts of them begin to surface. So yes, I’ve always been fixated on characters under immense pressure, people who are trying to find oxygen in a choking environment.In The Fire and The Moth, I think Saba is also sprinting for some sort of survival, but he’s given in to the sickness of greed, he doesn’t care anymore even though his desires start from love. It’s the same thing I tried to explore with Opa, Teriba, and even Abike. These aren’t villains; they are Nigerians doing mental math every day between what they know is right and what they think will help them survive. And that, to me, is where the heart of our national crisis lies. Not just in the people who are obviously corrupt, but in the everyday, subtle erosion of conscience that happens when the system grinds you down. We need to have a national discourse.

AAdedayo: As creatives, it appears that when we create, we create because we want to show something, say something, turn the world toward something. However, because the curve of learning is not linear, people miss the point. What do you believe is the most important thing you want viewers to see in your work?

Taiwo Egunjobi: I think first of all, I’m really intentional about making interesting films, I don’t believe in boredom so that’s central to my goal but the core of my consciousness is really about this internal debate I’m having with myself that we are not okay and that pretending otherwise is part of the rot. I think I’m constantly trying to hold up a mirror that doesn’t flatter, that shows us as we are. There’s deep cultural corrosion, and I’m really interested in exploring these things and presenting them to the audience. I remember watching films like Saworo Ide, Koseegbe, or Muyiwa Ademola’s Owo Okuta, and feeling uncomfortable about what they had to say about us and to us, and I really value that. If people see my films and they come away slightly disoriented, maybe even a little guilty, then I’ve done my job.

Adedayo: Our lives are intricately tied to the people and the place we come from, and the idea of sabotage is often at the expense of the people we strive for. Look at Saba and his father. Look at Abike and her sister. Or even the policeman and his daughter. What are your philosophies on human life, who it is connected to, and how do your philosophies shape your eye for film?

Taiwo Egunjobi: I’m constantly struck by the verse “they sow the wind, and reap the whirlwind”, a scriptural truth that echoes through both my Christian sensibility and Yoruba cosmology. In both worldviews, actions ripple through time and space, touching bloodlines, communities, and futures not yet born. What we plant—whether love, betrayal, ambition, or neglect—never returns to us untouched. It magnifies, spirals, and sometimes returns as a storm. You find it symbolized by the Afopina, the moth that seeks to put out the flame in the lamp. Afopina only kills itself. In The Fire and The Moth, these characters aren’t just fulfilling character arcs; they’re echoes of spiritual and cultural cause-and-effect.

My philosophy on human life is rooted in this: that we are part of a moral and metaphysical ecology. And those stories, particularly in film, can serve not just as entertainment, but as mirrors and compasses. I believe that higher art must strive for higher thought and, from there, inspire cultural reformation. I seek to entertain, yes but beneath that, my deeper drive is threefold: to provoke thought, to restore meaning, and to disturb complacency.

Adedayo: In a recent interview on West Africa Weekly, you said the title image, a fragile creature fluttering toward what will burn it, became the film’s compass. Classical Yoruba cosmology also warns that wealth attained without iwa (good character) inevitably scorches its bearer. When you framed Saba’s final stumble through the burning kola‑grove, were you staging a visual proverb, or did you lean more on neo‑noir fatalism from the Tarantino side of your influence map? Are there visual cues you want the viewers to look for?

Taiwo Egunjobi: I’ve always loved how Yoruba cosmology doesn’t separate the spiritual from the moral; you can’t escape the consequence: a man chasing treasure with no spiritual license to carry it. The final image of the film is us creeping up on the bronze head fallen just behind the man who carried it as plunder; the focus has shifted from the man, and it has returned to the bronze head; the final image is judgment.

Adedayo: Taiwo, I really enjoyed this movie. Hollywood has a habit of tinting the Global South in shades of colonial unease: Denis Villeneuve’s Sicario drapes the El Paso–Juárez border in dust‑blown sepia, framing Mexico as a sun‑bleached arena of cartel violence, while a wider “orange‑teal” fashion codes Africa and the Middle East as perpetual heat and hazard. By contrast, Tunde Kelani soaks Yorubaland in ochres, indigos, and festival reds that honor its textile and earth pigments. The Fire and The Moth chooses a different register again—terracotta smoke, mildew greens, the muted turquoise of oxidized bronze—echoing the patina of the Ife head at its center and the rusted roofs of harmattan‑dusk Ibadan.

Did your colorist literally sample hues from the bronze’s turquoise pits and copper flares, or were you chasing the damp reds and sickly greens of Tin‑roof Ibadan? Can you briefly talk about a LUT tweak—or one on‑set lighting choice—that stitched that heritage pigment to contemporary grime, and tell us how you avoided the “sepia‑saves‑the‑world” trap while still signaling class, desperation, and slow violence.

Taiwo Egunjobi: Absolutely, thank you, and I’m so glad the textures of The Fire and The Moth spoke to you. Color was central to how we grounded this story. While I deeply admire both Sicario and Tunde Kelani’s painterly use of pigment, especially his ochres and indigos, we knew from the start that we wanted to avoid imposing too much of a stylistic filter on top of the environment. Our guiding philosophy was environmental realism: letting the land speak for itself, not color-grading it into something else.

We were shooting in deep forests, green hills, dusty red clay roads, houses half-swallowed by trees, and dusty, lime-washed interiors. These spaces already had their own palette; mildew greens and rust-reds, so we played around with that. Conversations with the colorist Stedi and DOP Fadamana were often about finding the right type of browns and reds, and it began months before shooting; all of these are part of my holistic color program in my production design, which is a department I lead myself on film projects.

One lighting decision that really stitched it all together was our DOP’s choice to abandon “natural moonlight” and instead light night exteriors with a harsh sodium streetlamp feel. That yellow‑orange burn found its echo in the interior practicals too.

In avoiding the sepia-trap, we trusted the land’s palette. No global South wash, no “teal-and-orange” shorthand. Just the colors that were already there, seen clearly. While I was in my way inspired by the spiritual and visual philosophy of the Coen Brothers’ No Country for Old Men, we set out to coin a visual language true to our environment, maybe something we’ll call an Afro western.

Adedayo: Thank you, Taiwo. At the end of the movie, two images linger: the bronze head, its turquoise blemishes still aglow, exerting the “spiritual gravity” that you described, Taiwo. The second is the moth forever spiralling toward flame, not just in this film, but even in my own poems. Between them lies the moral territory of The Fire and The Moth, where colonial plunder mutates into everyday hustle, and where each of us must choose whether to carry history as inheritance or contraband.

If the film unsettles you, consider that its achievement. Restitution is more than a diplomatic headline; it is a reckoning with the habits of greed we harbor—then normalised—since 1938, when the first Ifẹ heads were hustled aboard steamers in Lagos harbour. The story also interrogates the japa impulse: will mass flight end in escape, or spur deeper questions about why escape feels necessary at all? And, by recalling the proverb afòpiná tó ní ó pa fìtìlà, ará ẹ̀ ní yóò pa—“the moth that tries to snuff the lamp kills only itself”—the film warns that any nation eager to dim its own light risks being the first to burn.

Taiwo Egunjobi is a Nigerian screenwriter and film director.

Inspired by the works of Yasujuro Ozu, Tunde Kelani and Quentin Tarantino, Taiwo Egunjobi started writing and producing short films as an undergraduate and continued as a screenwriter in the Nigerian Film Industry, writing screenplays for films such as Gidi Blues, The Grudge and Sidi Ilujinle, working with Femi Odugbemi and Tunde Kelani.

His debut feature film, In Ibadan premiered at Zuma Film Festival in December 2020, receiving a nomination for Best Actor. It also won the Best Film Award at the Kwara Film Festival. His second feature film All Na Vibes, was the Opening Night Film at the Nollywood Week in Paris Film Festival in March 2021 and also screened at the International African Film Festival in Argentina in October 2021. His third feature film A Green Fever premiered at the African International Film Festival in December 2023. The Fire and the Moth is now streaming on Amazon Prime.

Adedayo Agarau is the author of “The Years of Blood,” winner of the Poetic Justice Institute Editor’s Prize for BIPOC Writers (Fordham University Press, Fall 2025). He is a Wallace Stegner Fellow ‘25, a Cave Canem Fellow and a 2024 Ruth Lilly-Rosenberg Fellowship finalist. He is the Editor-in-Chief of Agbowó Magazine: A Journal of African Literature and Art and a Poetry Reviews Editor for The Rumpus. He is the author of the chapbooks “Origin of Name” (African Poetry Book Fund, 2020) and “The Arrival of Rain” (Vegetarian Alcoholic Press, 2020).