Editor’s Note

I have been writing a story in which my character is struggling to remember. He is a teacher who lived through the Civil War, a man from Ibadan—the city where I grew up, the city where Agbowó found its purpose. I am stuck writing this story at the point where my character, who carries the full awareness of himself, transitions into that void where he no longer remembers. That void the world has come to know, one without the history and stories that help us trace our own pasts, or the possibility of what is to come.

I have been rewriting that scene—where the tragedy arrives and my character shuts down, where the words should begin to crumble before him—not because I do not understand what it means to forget. I am a memento of my own forgetfulness, and my body is a testimonial. I believe we all know forgetting intimately in this part of the world, where erasure teeth our historical collectives, where amnesia is sometimes the only mercy left. But I am stuck because transition, this kind of transition, is where meaning lives. That cusp between knowing and unknowing, between archive and the echoes that come back when you scream into the void.

That is where Agbowó has always existed.

Since 2017, Agbowó, which started as a collective of University of Ibadan students and alumni, has taken on literary stewardship with the mission to preserve the most authentic African stories. We began this work precisely because we understood that African literary art was disappearing into a void. We watched brilliant work get lost in the noise of the internet, fade in journals that couldn’t sustain themselves—Glendora Review, Saraba, Expound Enkare, Farafina, Praxis—or, worse, never get written at all because writers couldn’t find a home they believed was for them.

My work at Agbowó has now come full circle. I have been travelling the American West since September, and this past week, I read in Decorah, a small town in Iowa. It was in Iowa, sitting in my small, shared apartment in Coralville as it snowed outside in December 2021, that I curated my first issue as Editor-in-Chief. Now, I am in Los Angeles, in a large room with large windows, and it is Agbowó’s 10th Issue, my final delivery.

The writers in this Issue understand this same tension between the present and the past that is disappearing. What happens to a name when it crosses the room? My Iowa roommate called me Adi instead of Ade, and in Winifred Òdúnóku’s “Hello World,” a voice arrives with a riddle: “How did you get here?” The story answers with its own staged astonishment. An old woman pulls a spear from her chest and tosses it aside, barefoot, unflinching. Fiction, here, is instruction. It asks what a body can hold without breaking, how the self steps back into the world after being written off.

This poetic tension is echoed across the issue. In Osahon Oka’s “Before I Perish,” the speaker, “rejected and detached,” finds that “there was no grace to be had here or there. / It was war… yet war and nothing.” To survive, he must become Orpheus, to “Creep into tomb and sing messiah awake.” This act of pulling history from the void is a job the poet takes seriously. Ismail Yusuf Olumoh, in his “Epitaph…,” becomes “an historian, / uprooting the archive of every aged man in my bloodlines,” learning how “the tree learns to root / in its own fire.”

Where Oka and Olumoh build an archive against the fire, Naomi Nduta Waweru finds resilience in the smallest details after it. “In the year of the rainstorm, the dew still floated on the leaves,” her line insists, as if to say the return to the self is a recurrence, a ceremony of moisture. If Òdúnóku’s story tests the tensile strength of endurance, the poetry in this issue provides the answer: we survive by becoming historians, by singing in the tomb, and by witnessing the persistence of the world’s smallest waters.

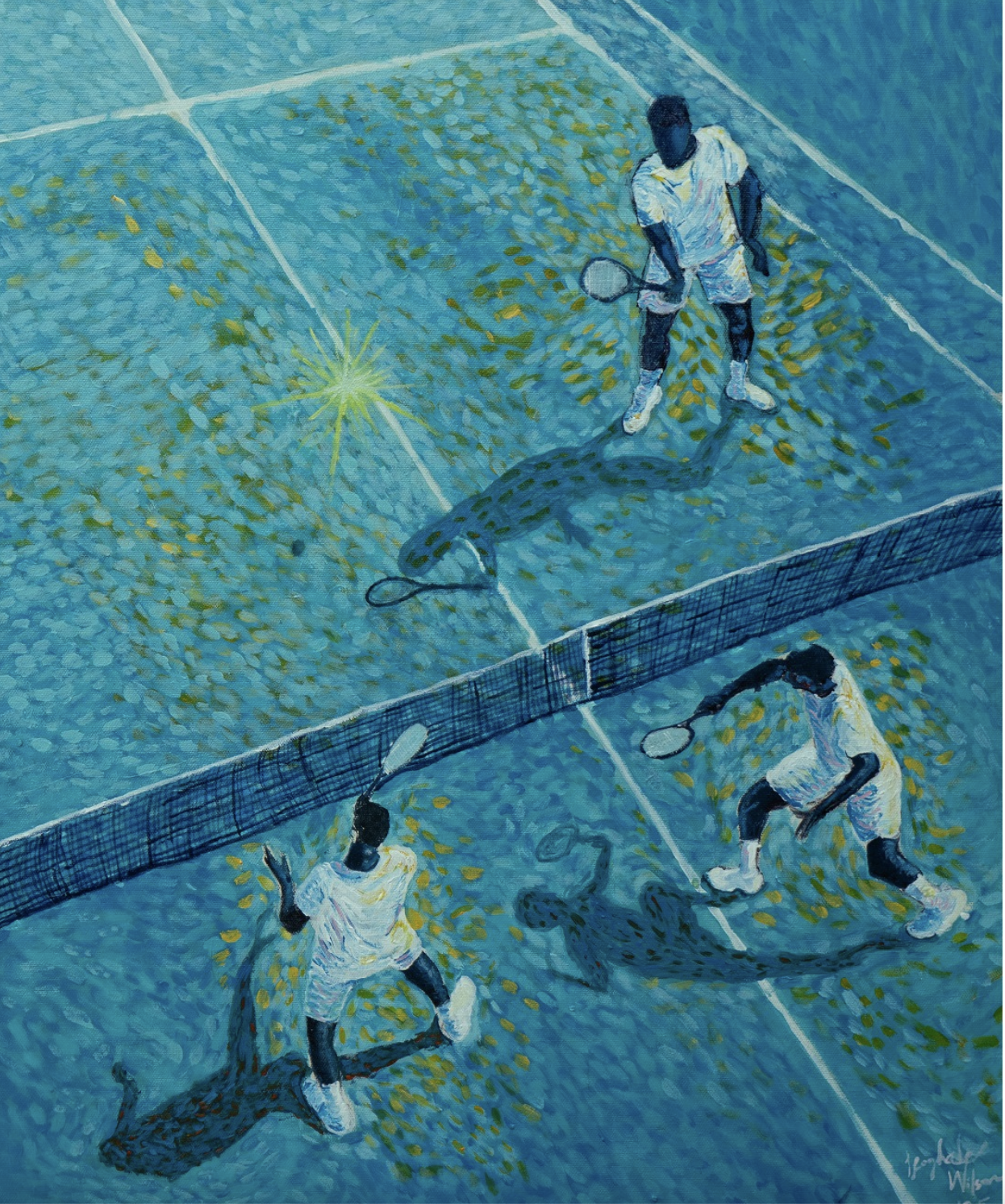

This theme is picked up in “Arriving Nowhere, Everywhere: On the Art of Ifoghale,” which presents a wind-swept field where cloud-shapes “advance like restless migrants.” The interview interrogates the modern vocation—”The problem was I took issue with modern life and its definition of work”—and suddenly we are back at the threshold between what life demands and what the self requires to remain whole. Adaeze Okaro’s photographs deepen this conversation about the intimacy of the self with itself. Her images are a discipline of care, a practice of holding light for a life discovering itself. Faces are not posed so much as permitted. Adaeze’s work is the labor of attention, the worth of keeping, the silent party in domestic bedrooms. What is a camera if not a small archive that clicks at the perimeter of forgetfulness? What is framing if not a vow to return to the body what history has taken?

“The Illusion of Freedom” by Idowu Odeyemi employs sentences that are merciless and clear: “We think we are free, and we want to be free, but we are not.” What does a painting of transit say to a paragraph about entrapment? That a horizon can be a mirage, that arrival can be a myth disguised as a map, a jailer made up as a cartographer. The essay argues that the mind itself is a workplace colonized by history. And suddenly, Ifoghale’s refusal—”I didn’t want or like that,” about the prescribed life—becomes not just an aesthetic choice, but a strategy for survival.

As I close this chapter, I want to extend my deepest gratitude to the masthead for their incredible work: Habeeb Kolade, Darafunmi Olanrewaju, Joba Ojelabi, Maxwell Dewunmi, Nome Emeka Patrick, Hauwa Nuhu Shaffii, Adams Adeosun, Uthman Adejumo, and Moyosore Orimoloye. My thanks also go to our readers, for always returning to Agbowó and helping us build this community, and to our board, for their unwavering trust.

Adedayo Agarau

Cover Art by Adaeze Okaro – Genesis

WORKS

FICTION

NON FICTION

POETRY

VISUAL ARTS

Adaeze Okaro