ISSUE 5 | JULY 2022 | REINCARNATION

247 seconds.

She counted. Each one connoted by the tick of the second hand of Bernard’s watch that came to her like a heartbeat from the centre of a frantic cosmos. The sound echoed in spaces inside unknown, unexplored parts of her that felt raw. It shut out everything else, blurred it almost to nothingness, drowning her in a hollow world. All that remained was the smell; odd in this vacant, foreign echo of a home, the smell of guava with the faintest hint of something nauseatingly metallic. She clung to it, pulled on it desperately, hoping that it was tethered to something on which she could find her footing, something to anchor her and stop her floating deeper into a darkness that threatened to rip her apart, on one side, pulling her back to the past, bitter, screeching obscenities at her for not knowing any better and another one, predatory, silent, malevolently obscure, sought its pound of flesh from the future. The baby, her baby, getting colder and more limp with each tick, stood in between those two doomed parts of her and enveloped her in a mist through which she could not find herself, only vaguely felt her own presence somewhere far away, far below. She gasped for air and the guava and metal filled her lungs. With each second, the small bundle in her arms felt heavier until her arms began to cramp. After 247 seconds, a figure cloaked in white prised her arms apart and plucked the empty shape of new life from her arms. No matter how hard she tried, she could not remember what it looked like. It felt like something that had loomed on the periphery of a particularly bad dream, haunting her, always out of sight. All that was left to remind her of it was the phantom weight in her arms and that smell of guava and metal.

There was no ceremony to ornament her grief. There was no gathering to wrap her agony in the sympathy of fellow mourners, to serenade her suffering with the keening wails of women who wept, not for what she had lost but for her loss. The closest thing she got was a vague recollection of the other children that had been born in the ward, that had opened their little mouths and felt, for the first time, the weight of oxygen in their lungs, something hers had not done, would never do. There was no wooden box in which to fold her loss, twice, thrice, four times, and squeeze it in, so that she could bury it in the ground and let time putrefy it to a memory. There is only the emptiness that her tears cannot fill, carving out her insides until there is nothing left but a withered exterior that deflates and is carried by the wind through days that she cannot distinguish from one another, feeling as if she has lived each one before and barely able to withstand the thought of having to go through another one. She mourned alone. There are no funerals for those that never lived. But what they could not understand was that he had lived. He had lived inside her for seven months, two weeks and five days. She had nourished him, had felt his powerful kicks, felt his strength, a mirror of his father’s, in the vigour of his movements. She had sung to him and spoken to him. She had listened to the sound of his heartbeat at the ultrasound scans where the doctors had told her that she had a healthy baby boy. Healthy. Can you say that of something that was not alive? So how then could they say that he had never lived?

Searching amongst the rubble of her mind for some respite, she found a saying, something she had read in her university days that had struck her and she had written it in her journal when she still had time to keep one, when the naivety of not yet having sunk to the depths of true loss where even the sun could not reach, assured her that words could heal, “Grief is felt, not so much for the want of what we have never known, as for the loss of that to which we have been long accustomed.” She turned it over in her mind. She analysed its smooth surface with the stark clarity of newfound perspective, one born of suffering, and saw for the first time, the thin cranks, the notches, the dirt. She crumpled it and flung it furiously back amongst the rubble.

The sun set and did not come out.

She went to sleep.

Something startles her awake. Reluctantly, she emerges from a dreamless slumber, and the dimness of an unfamiliar room slowly blurs into focus, causing her mind to reel in panic until she finally recognises the framed ultrasound image on her nightstand. Suddenly, there is a sound from behind her. Initially, she cannot place it, but gradually, as the confusion of wakening wears off, comprehension dawns on her. An invisible hand grips her heart. It is the soft cooing of a baby. At first, it seems to come from right behind her and her hand is instinctively drawn towards it. As she reaches out, it retreats from her. She feels a wetness on her chest and when she looks down there are two dark circles on the front of Bernard’s t-shirt that she sleeps in. She looks on his side of the bed and doesn’t find him. A thin column of light beams from the slightly open door of their ensuite bathroom, casting a pale glow on the room in which shadows dart in and out of sight. Bernard? He doesn’t answer. The cooing becomes a cry. She slides out of the blankets and winces at the coldness of the floor on the soles of her feet which makes her instinctively curl her toes. Dragging each heavy, cold foot, she follows the sound towards the bathroom door, the crying getting louder with each step, each fluttering heartbeat. She tentatively pushes the door open and a blinding white light floods her eyes.

Babe?

She whirls around, blinking rapidly. Bernard is sitting up on the bed and has turned on the bedside lamp. The veil of a shadow on his face fails to conceal the worry in his eyes. She turns around to face the bathroom again. Darkness. And silence.

Are you alright? His tone suggests that he has already decided she is not.

A warmth collects itself in her tired eyes, drowning the world around her, Bernard, the framed ultrasound picture, even the darting shadows, before it finally trickles down her cheeks, washing away any strength she had left.

She shudders and wraps her arms around herself. She is only distantly aware of herself as she silently walks into the darkness of the bathroom, not bothering to turn on the light, and closes the door behind her.

When dawn finally comes, it is tinged with a luminescent melancholy that renders the world bland. It finds her in a near catatonic state, crumpled among the broken shards and torn pieces of the ultrasound picture.

The days that follow go by like the faded memory of a dream. In it, she feels his presence just beyond the scope of her vision. Even though she cannot see him, the charge in his accusing glare makes her hairs stand on end. She remembers all the small things she had done during her pregnancy, thinking they were harmless. She recalls the night that Bernard had come home and she had been feeling particularly prurient. She had followed him into the shower and when he gave her a questioning look, she had reassured him that it was ok for couples to have sex during pregnancy. The doctor had said so. The same doctor who pronounced him dead before she could hear his first cry. She recounts the single glass of wine she had on their anniversary when Bernard took her to Manna Resorts and to his eyebrows that rose in question, she smiled and said the doctor had said that a little bit of wine was harmless. The same doctor who took his lifeless form from her to dispose of like some unwanted waste. She thinks of all the luggage she had carried, insisting that it was not heavy when Bernard offered to help. Every ‘I’m not that pregnant’, ‘The doctor said it’s ok’, ‘I can still manage’ rang out in her ears until they began to ring, a high-pitched tone which crescendoed into sobs that she only realises after a while, are her own. You did this. She is not sure whether the voice she hears is her own or that of his figure looming behind her.

From somewhere far away, she hears Bernard’s voice. It is a continuous hum through which she only manages to hear her name. She feels his hand on her shoulder and recoils. When she turns to face him, he is dressed for work. Work. Yes. She must return to work. It will take her mind off things. She does not know whether she has said it out loud or in her head but Bernard shakes his head and says something. It sounds as if he is speaking underwater. He takes a step toward her. And then another. He always kisses her on the cheek before he leaves for work. He gets close enough for her to smell the woody musk of his Dior Homme cologne that she had gotten him on their anniversary. Instead there is that smell again, and she feels the contents of her stomach rise. She closes her eyes as he leans forward, and waits for the feel of his soft lips against her cold skin. There is no kiss. Instead, she hears a whisper. You did this. She gasps and opens her eyes. Bernard is waving at her from the door, smiling. He turns around and leaves.

She gathers what little of herself she can salvage and collects it into an imitation of salubrity before she gets ready.

On the day that she goes back to work, a limp sun sits like a dying fire in the sky, hovering purposelessly. The day is draped in a thick fog that turns the shapes and figures around her into phantoms. She had not been able to find her car keys, so she decided to walk the distance from their home in Strathaven to their offices in the Avenues. In the city centre, the ghosts of work goers shuffle around her, sinking her with their gazes that are clouded by something that unsettles her, a knowingness, as if they could see something on her that she wished to hide. The figures speak in hushed tones as they walk past her and she feels their pointing fingers and judgemental eyes on the back of her neck.

Even without turning around, she feels him close by, watching through the crowd, waiting. A cloud passes overhead. Someone in the crowd laughs. And then another. The laughter spreads like a contagious disease and soon, everyone in the crowd has caught it. She, too, catches it. She beats her chest and keels over and laughs until tears fill her eyes, until her ribs begin to hurt. The sun too, joins in the laughter, the clouds, even the trees sway wildly as the mirth possesses them.

When she walks into the office, she sucks all the sound from every room she passes, leaving vacuums of pity that, more than anything else, feel professional. They watch her like a fragile, precious artifact that is hurtling in mid-air, part of an act by a daring juggler, visibly holding their breaths.

Someone she does not recognise comes up to her. The person speaks to her in a commiserative tone, their head weighed to one side by their sympathy.

How are you feeling? Are you sure… It’s okay if… Just let me know…

She nods her head in response to their questions but her tongue is unable to extract words from the void her mind has become. The figure raises its arms and embraces her. They tighten around her until she can no longer breathe.

She pushes the intruder away and runs to the bathroom, the world whirling vertiginously around her. As she slams the door behind her, she hears them shout, Murderer!

She comes to a sudden stop when she hears the honking of a car from a distance. She is standing in the middle of the road. She looks around disconcertedly. The driver of the car is gesturing at her angrily through the window. She stammers and then stumbles to the edge of the road.

Through the fog, she makes out the silhouettes of two figures sitting under a tree. She inhales. Guavas. She approaches the makeshift roadside stand of cardboard and stones. An assortment of fruits and vegetables is laid out on top in pyramidal heaps. There are apples, bananas, tomatoes, onions, collard vegetables… and guavas.

Without looking, she knows he is behind her. Even though he has no form because her memory cannot fashion one, she knows him from the scent he carries, that odd mix that had filled her nostrils when she held his lifeless body to her and kissed his head. He is a void in the ether, a hole in the threadbare fabric of her world, a heaviness in the air. He comes closer. She is paralysed, tethered in place, helpless.

He reaches for her.

She shuts her eyes and waits for something she does not know but that she is ready to accept.

There is a tug on the sleeve of her blouse. When she looks down, a pair of small eyes are looking up at her. One hand is on the sleeve of her blouse and another one is stretched out towards her face. Even standing on tiptoes, the small figure can only reach as high up as her chest. Its little hand is wrapped around an object that it is offering her, a partially eaten guava.

Don’t cry, you can have it if you want.

It is only then that she feels the tears on her face. She hurriedly wipes them with the back of her hand.

The small figure is still looking up at her expectantly. She holds out her palm and it hands her the guava. She brings it to her nose and takes in its scent.

Are you ok?

She is startled at the sound. She lifts her head to see an elderly woman staring at her, the little boy’s mother. She notices that the fog has cleared.

“Yes, I’m alright. Everything is alright.”

Would you like to buy anything?

“How much are these?” She gestures with her hand.

The little boy smiles at her. She smiles back and takes a bite of the guava.

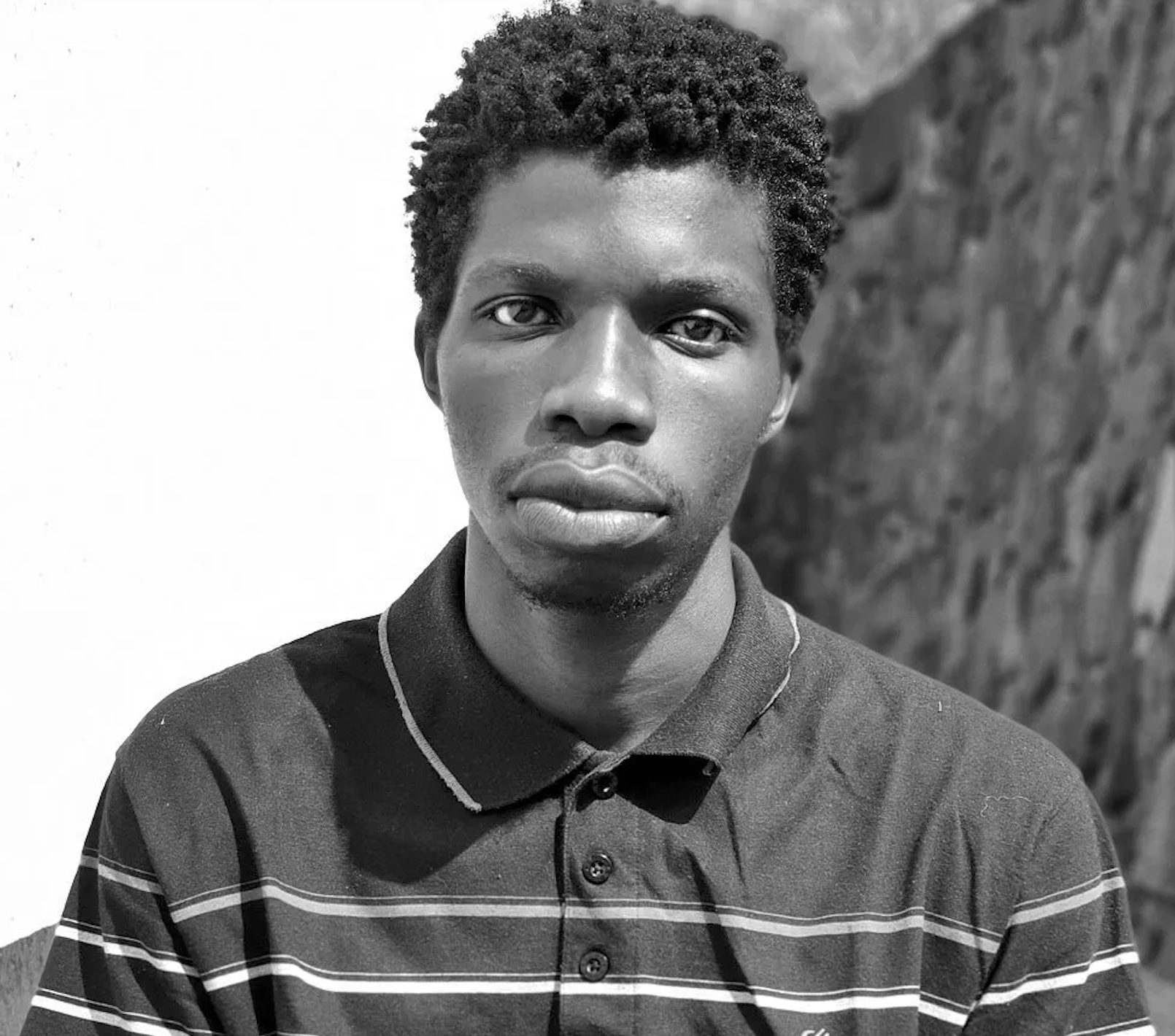

Lazarus Panashe Nyagwambo

Lazarus Panashe Nyagwambo is a Zimbabwean writer and freelance editor. He is the author of the short story collection, ‘A Hole in the Air.’ His works have been published in several literary magazines including AFREADA, Omenana and The Shallow Tales Review. He also contributed to the anthology, ‘Brilliance of Hope.’ He writes from betwixt the four walls of his solitary bedroom in Harare, which unbeknownst to his family, is a portal to many worlds. He is currently flirting with the idea of a full-length novel and tweets as @LazarusPanashe.

Photo by Marek Piwnicki on Unsplash