DOWNLOAD THE REINCARNATION ISSUE HERE

WORKS

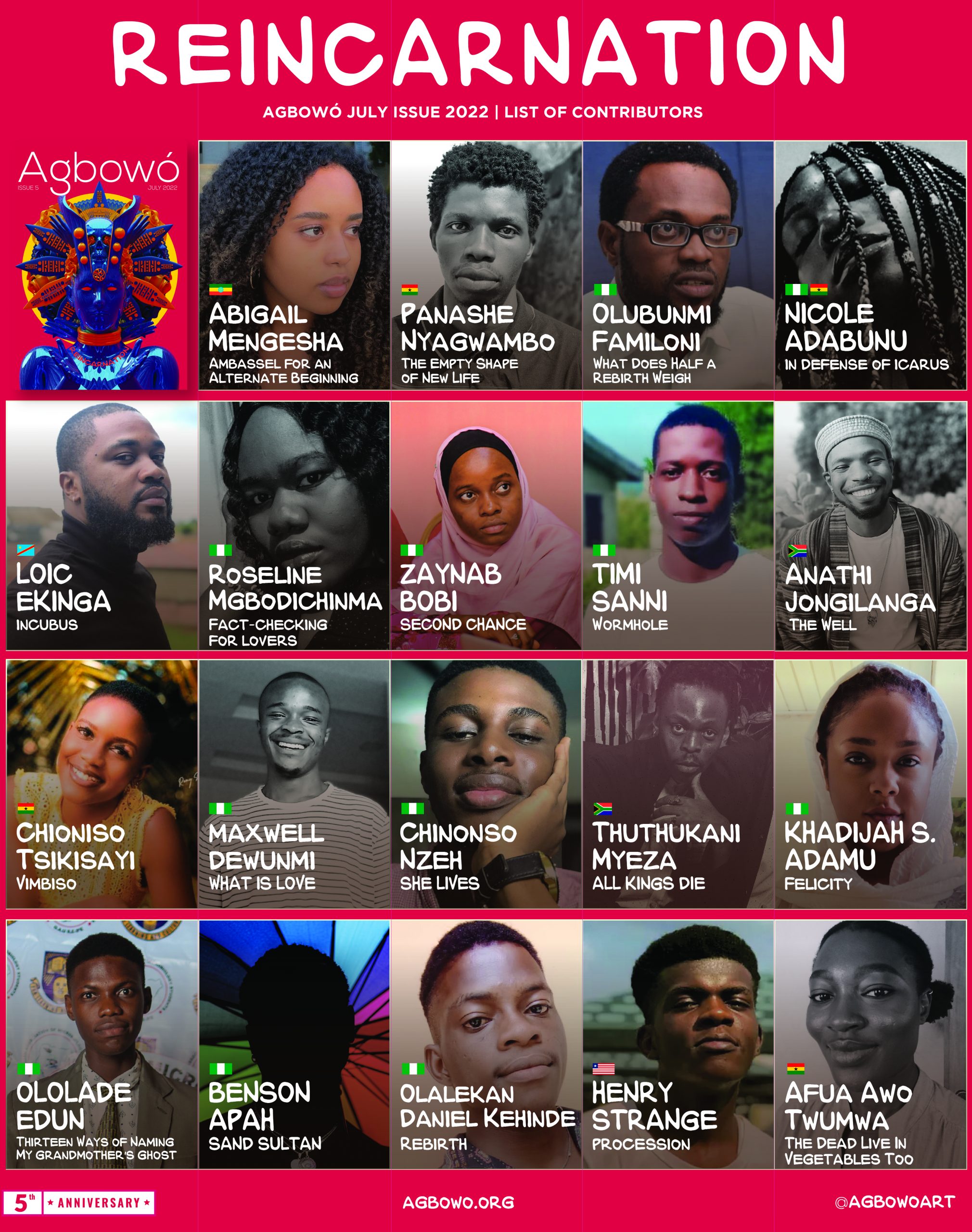

DRAMA

Olubunmi Familoni

What does Half a Rebirth Weigh

Nigeria

FICTION

Anathi Jongilanga

The Well

South Africa

Loic Ekinga

Incubus

DR Congo

Chioniso Tsikisayi

Vimbiso

Zimbabwe

Panashe Nyagwambo

The Empty Shape of New Life

Zimbabwe

NON FICTION

Chinonso Nzeh

She Lives

Nigeria

Khadijah S. Adamu

Felicity

Nigeria

POETRY

Abigail Mengesha

Ambassel for an Alternate Beginning

Ethiopia

Timi Sanni

Wormhole

Nigeria

Roseline Mgbodichinma

Fact-checking for lovers

Nigeria

Nicole Adabunu

In Defence of Icarus

Nigeria-Ghana

Afua Awo Twumwa

The Dead Live In Vegetables Too

Ghana

Henry Strange

Procession

Liberia

Ololade Edun

Thirteen Ways of Naming my Grandmother’s Ghost

Nigeria

Olamilekan Daniel Kehinde

Rebirth

Nigeria

VISUAL ART

Maxwell Dewunmi

What is Love

Hollow

Severed

The Monarch

Twilight

Nigeria

Apah Benson

Sand Sultan II

Sand Sultan III

Spectra I

Spectra II

The Quest

Nigeria

Zaynab Bobi

Second Chance

Rebirth

Nigeria

Thuthukani Myeza

All Kings Die

Gates

Indoda

irrelevance of form

South Africa

INTERVIEW

Maxwell Dewunmi

Maxwell Dewunmi

Apah Benson

Apah Benson

Editor’s Note

During a guest reading at the Iowa Writer’s Workshop, Carl Philip said, “the comma is an element of surprise, the stride towards something possible.” This was after I had asked him about the function of a particular comma in one of his poems. In this issue, our contributors have done what the comma does, according to Carl Phillip. Agbowo, after five years of excellent aesthetics, puts a comma—a stride forward—to its story with Reincarnation. It re-emerges with new editors and readers, with a common goal of publishing what we perceive as today’s African writing. The truth is this issue has betrayed the goal because what we have collected is futuristic—a tomorrow’s story—what emerges from the smoke of African Literature. In what we know as the alternation of existence or the perseverance of self, reincarnation brings an ambiance of confusion or mystery to the light. However, the simplicity is in these poems, stories, essays, and drama.

In what other way can life exist after it has existed? Emergence, a synonym for being: in the hurtling syntax and uneasy metaphors presented in this issue, has rightly shown us what oblivion means without having to experience it. According to Olubunmi Familoni in What Does Half of a Rebirth Weigh, reincarnation exists outside the limits of time. The drama cultivated scenarios of spiritual exchange—what happens in the sequence of delay? What do the spirits require of the child before they let it towards its mother’s womb? The father, the husband, the grandfather? What is the cost of our lives? Reincarnation as a question may not have been answered in this issue, but it has issued us light towards the tunnels of oblivion.

In Cinematic Orchestra and The London Metropolitan Orchestra’s rendition of Transformation, something struck me the most—the lingering of the grand piano, or was it the reverberance? Not the chiming strings, the resonating chords, the lingering vibrato of this grand piano. The grandeur that I speak of resembles the elegant Jacksonville sun on a lazy Saturday. The palm trees outside the window sway until Bon Iver’s Holocene plays from the stereo. This ambiance is what Henry Strange’s poem, Procession, plants on the terrace in this issue—how the poem is in constant interrogation of sound and sonics—how it corroborates the vibrance of mastery of Anithi’s storytelling. I look towards display, the magic that literature performs, the world it builds us both in music and out of it. Procession speaks of a door unspoken of, a gateway towards exchange. And in this exchange, or rather, a transaction, because there is something sometimes snatched and not taken, there is “a father returning,” or Babatunde as the Yorubas will call it, waiting to be mentioned in Olalekan’s Rebirth.

Reincarnation as a theme is making the past available for the new world—the world where cars fly and where writers like Abigail Mengesha can alternate beginnings. While what we collect is towards the future, we also have attempted to bring you grief. Or maybe this is hope that death is not the end of things—that someone’s dead child will be reunited with their mother in the opening of the doorway—and that the door does not mistake an apple for an orange tree.

I am happy to present you with the best African writing today. An issue of prose and poetry that can withstand time & explain and reexplain grief and loss as a mere passage or a shift in time, rather than wound as we used to imagine. And by imagination, these works have put through the prisms of imagery what possibilities there are for the body & the souls that wander without it. But also, what others portals can open and can alter the concept of time? Love, family, mental illness? Maybe this issue has more light to shed than grief. Maybe what burns the house/the body isn’t the smoke but the intention to set something on fire—what emerges from the fire & does it emerge unscathed? Adabunu’s poem presents a different light—with a form that reminds self of the tower of Babel or at least the intention to see God. What depth of spirituality was displayed in Vimbisio? What other forms of spirituality did Nicole point us to in her poem? What wonder has Panashe done? How is Loic ending the narrative of loss? What wonder is waiting for us in the dark of his story, Incubus?

Is it true that there was a uniform intention to see [g]od—or what each writer perceived it to be, throughout this issue? What use was language put to in Ololade Edun’s Thirteen Ways of Naming My Grandmother’s Ghost? How did Chinoiso define healing in her striking story, Vimbisio? Is the journey of healing a journey towards [g]od?

I lead you into this issue—towards the seas that carry the spirits that drive these stories—towards every story, every poem—and into the heart of the writers.

Adedayo Agarau

Iowa City,

July 2022